Unions are powerful in Illinois, and the state allows them to sign contracts with employers that force all workers covered by these contracts to either join the union formally and pay regular dues, or pay an “agency fee” in lieu of dues. This agency fee typically costs the same as regular dues and can be used for all the same purposes. Nearly every union contract in Illinois contains such a provision.

Forced dues finance a powerful union movement, which in theory should be a strong advocate for workers’ rights, winning them more secure jobs, better working conditions and more generous compensation. In practice, the agency fee has created unaccountable unions that have cost workers jobs and made it extremely difficult to address the state’s biggest problems.

The spectre of overly powerful, unaccountable unions causes many businesses to locate outside of Illinois, reducing the number of jobs and opportunities available to Illinois workers.

Union lobbyists and union-backed politicians have also made it extremely difficult to reform Illinois’ underfunded pension plans. Instead of restraining government costs, political leaders in Illinois contemplate tax increases that would drain even more resources from the state’s economy. This – not prosperity for workers – is what has been bought with forced union dues money.

Illinois’ economy is floundering, and conditions will get worse without decisive action.

Illinois is on its way to becoming a poor state:

- Between 2002 and 2012, Illinois was seventh from the bottom in GDP growth nationwide. Of the six state economies that grew less than Illinois’, only one had a Right-to-Work law.

- Employment in Illinois declined by 2.3 percent during that same period. Only four states: Michigan, Ohio, Rhode Island and New Jersey – none of which had a Right-to-Work law – performed worse than Illinois in terms of retaining and creating jobs.

- Wages in Illinois have flatlined, with the state’s median wage increasing by only 2.6 percent between 2009 and 2013. By comparison, the national median wage increased by 5.8 percent during the same period.

- Illinois is becoming a much less attractive place to live, as demonstrated by the state’s slow population growth. Between 2000 and 2010, the state’s population increased by only 3.3 percent, while population of the country as a whole went up by 9.7 percent.

- People are leaving Illinois in droves, and they are taking their talents and earning potential with them. Between 1995 and 2010, Illinois suffered a net loss of $35.3 billion in tax revenue due to a net out-migration of 855,196 people. Money that could have been spent or invested in Illinois instead went to states with lower taxes, and frequently states with Right-to-Work laws, such as Florida or Texas.

As much as Illinoisans might sympathize with workers and with the union movement, the state of Illinois must grow its economy. More economic growth means a larger tax base from which to fund government programs, while at the same time reducing need for many of those same programs. Strong eco- nomic growth would also ease the task of resolving the state’s pension problems.

Illinois is struggling with a stubborn, stalled economy. Powerful unions in Illinois have failed to promote solutions and in many cases have made matters worse. The economic record of Right-to-Work states is one of strong economic growth, which stimulates employment and lifts wages – precisely the prescription for what ails Illinois today. The state would benefit greatly from the passage of a Right-to-Work law.

THE SOLUTION

A state Right-to-Work law does not change labor law dramatically. A union that has demonstrated that it has the support of a majority of workers will still be recognized as their representative. Employers are still obligated to bargain in good faith with unions, who can pursue grievances and call strikes just as they can without such a law.

The main difference comes in union finance. Currently, almost every union contract in Illinois includes a clause stating that every worker covered by the contract must either join the union – and pay the associated dues – or, if the worker opts not to join the union, pay an agency fee in lieu of regular membership dues.

The practical effect when an employer agrees to an agency-fee clause is that the union is virtually guaranteed to receive union dues from nearly all workers.

This is not an appropriate guarantee for an employer to make to a union. It tends to make union officials less accountable to the men and women they represent. Workers who oppose the union’s political causes, or are frustrated with the union’s representation in the workplace, cannot ordinarily signal their disapproval by withdrawing support. Right-to-Work laws, approved by lawmakers or voters in 24 states, prohibit agency fees in collective bargaining contracts. This returns to all workers their ordinary First Amendment right to join a union or withhold their support based on their own convictions.

Just as importantly, Right-to-Work states are outperforming non-Right-to-Work states economically. This is especially true in terms of job creation. The record on wages is a bit more complicated, but workers in Right-to-Work states come out ahead in terms of purchasing power, and can look forward to even better wages in the future.

JOB CREATION

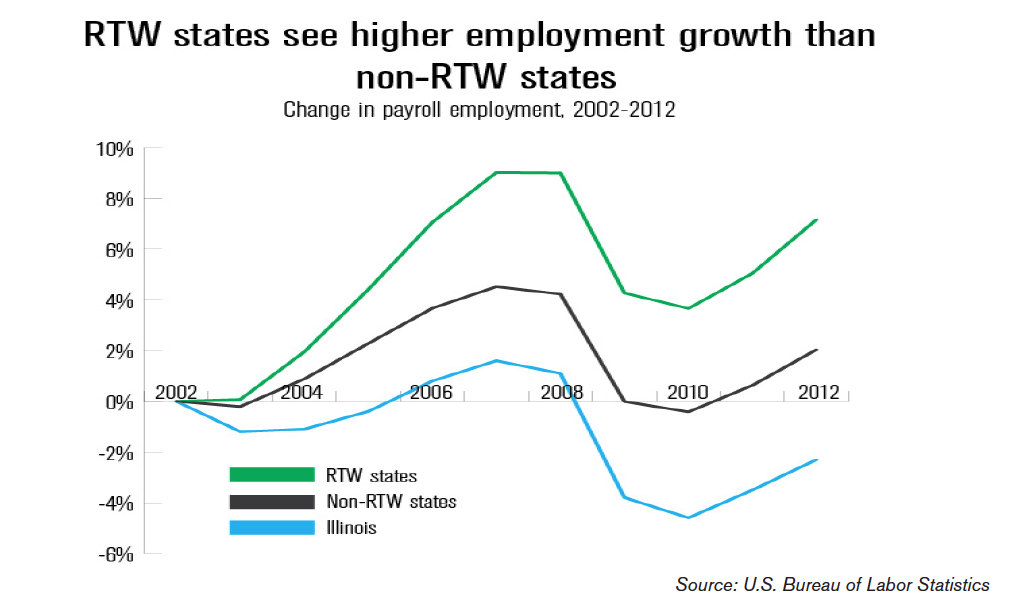

Right-to-Work states held a steady advantage in job creation and retention between 2002 and 2012. During that period, payroll employment increased by 7.2 percent in Right-to-Work states – in spite of the effects of the recession. In non-Right-to-Work states, however, employment increased by only 2 percent. Illinois workers were particularly hard hit during the economic downturn, with employment declining by 2.3 percent.

Steady employment growth means that workers in Right-to-Work states have lower unemployment rates. The average unemployment rate in Right-to-Work states was 5.5 percent in September 2014, half a percentage point lower than the 6 percent average for non-Right-to-Work states.

The unemployment numbers likely underestimate the value of Right to Work, however. The availability of jobs makes Right-to-Work states a magnet not only for businesses, but also for workers and families. Between the 2000 and 2010 censuses, the population of Right-to-Work states grew nearly twice as much as the population of non-Right-to-Work states – 13.6 percent versus 7.3 percent. Migration accounts for much of the difference here: Families are leaving for greener pastures, and these tend to be places where workers cannot be forced into sup- porting a union. This tends to make unemployment look higher in Right-to-Work states than it might otherwise be – it’s more likely that Right-to-Work states see new arrivals in the local job market who are looking for work at any given time.

WAGES AND PURCHASING POWER

On first glance, Right-to-Work states seem to be at a disadvantage in terms of purchasing power. Median wages in the average Right-to-Work state were $4,345 lower than they were in the average non-Right-to-Work state. But a closer look at compensation shows that Right-to-Work states are close to being on par with non-Right-to-Work states, and have an edge over the long haul.

First, nominal wages don’t account for local taxes or cost of living, which tend to be lower in states with Right-to-Work laws. When that is accounted for, the gap in wages disappears – or even reverses. The cost of living is 16.6 percent higher in non-Right-to- Work states, according to a state-by-state cost-of-living index compiled by the Missouri Department of Economic Development. This more than offsets the difference in wages; with cost of living factored in, median wages in the average Right-to-Work state were almost $750 higher in 2012.

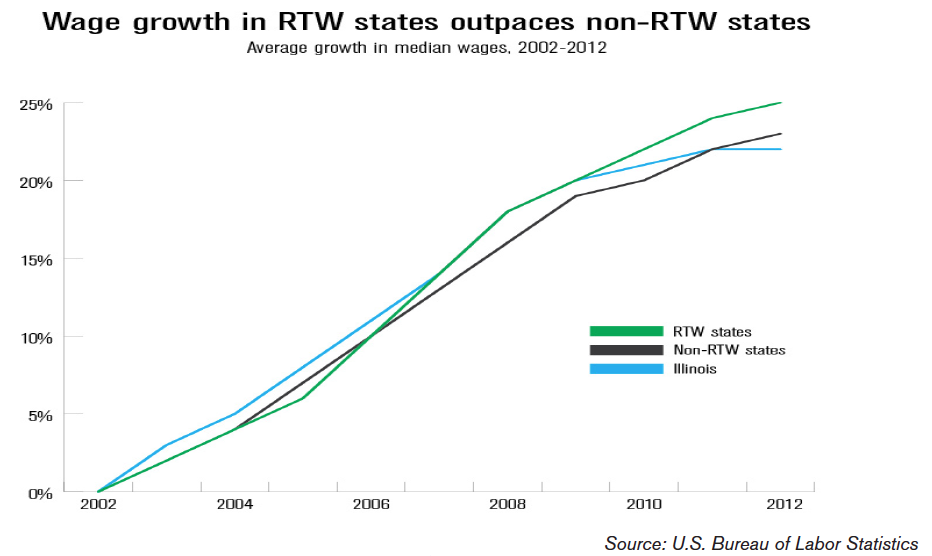

Even without taking cost of living into account, the gap shrinks over time. Between 2002 and 2012, wages grew faster in states where workers were free to decide for themselves whether or not a union deserves their support. The following chart shows the growth in median wages in Illinois, along with average growth for Right-to-Work and non-Right-to- Work states.

This is particularly important in Illinois, where wages have stagnated since 2009. In fact, Right-to-Work states are starting to overtake Illinois in terms of wages. As recently as 2008, median wages (not adjusted for cost of living) were higher in Illinois than they were in any Right-to-Work state. But wages in Virginia have been higher than Illinois since 2009, and median wages in Wyoming overtook Illinois in 2011. Both of these states have Right-to-Work laws.

Most Right-to-Work states were poor before passing Right-to-Work laws, but have since been steadily catching up in terms of both employment and wages. Illinois workers would benefit from the passage of a Right-to-Work law.

WHY THIS WORKS

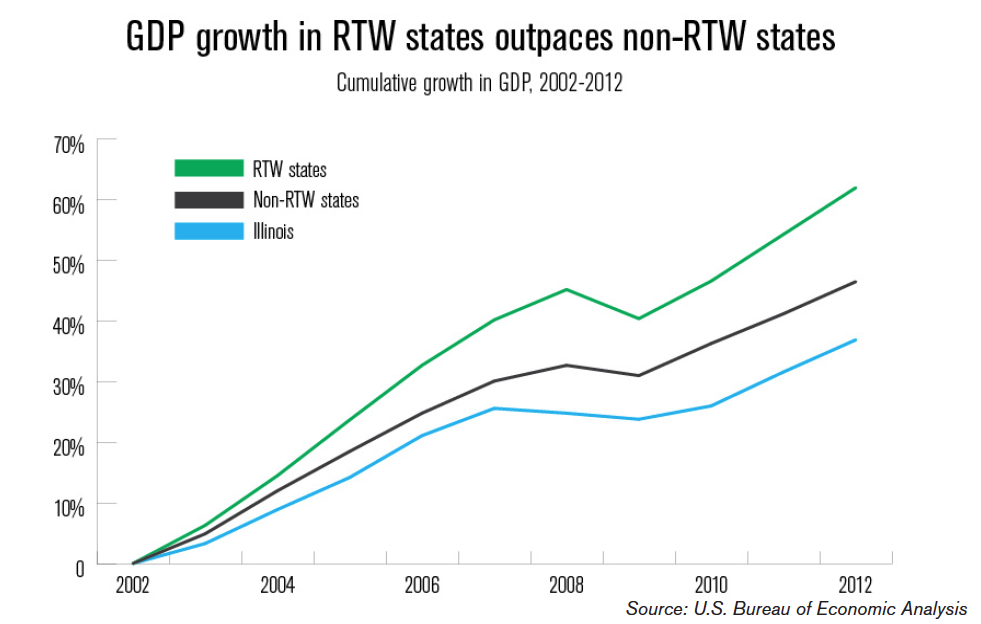

The key to understanding the value of a Right-to-Work law is economic growth, a measure where Right-to-Work states have held a clear advantage. From 2002 to 2012, the economies of Right-to- Work states grew by a total of 62 percent, compared to only 46.5 percent in non-Right-to-Work states. Illinois’ economy has been particularly sluggish, growing by a total of only 36.9 percent.

On average, throughout 2002-2012, economic growth in Right-to-Work states outpaced non-Right-to-Work states.

Aside from the statistics, there is a great deal of evidence showing that Right to Work stimulates economic growth. In 1997, University of Minnesota and Federal Reserve economist Thomas J. Holmes looked at areas where Right-to-Work states bordered non-Right-to-Work states, and found that manufacturing employment was one-third higher on the Right-to-Work side of the border. In addition, many experts in the site-selection field, who assist companies in finding locations for key facilities, have observed that many companies have a strong preference for Right-to-Work states. For some companies, the absence of a Right-to-Work law can even be a deal-breaker.

This steady advantage in economic growth drives every other major measurement of economic performance. It’s a matter of elementary economics: greater economic growth means higher demand for labor, as new or expanding firms look to staff their factories, shops and offices. Increased demand for labor means both more jobs and better compensation. The best situation for working men and women is a growing economy where opportunities are plentiful and employers are forced to compete to hire and retain workers. By attracting employers and investment, Right-to-Work laws stimulate economic growth to the benefit of all.

Unions can play a valuable role in allowing workers to present a united front to employers, in providing sound advice, and advocating for the rights of workers when they have legitimate grievances. Some unions also provide valuable training. But they cannot provide employment or wages. Even the best, most powerful union is not a substitute for a growing local economy in which jobs are plentiful. This growing, opportunity-rich economy is what Right to Work can offer the people of Illinois.